|

I don’t really think anything is ever black and white, completely good or completely bad. My latest CT scan, for example, was a mixed bag of news, even significant and insignificant. In a way, this helps me prepare for scans in general, if I believe that there won’t really be any extremes, or anything too shocking or groundbreaking. And then if there is, I get to be pleasantly surprised (or maybe unpleasantly blindsided, and I’ll cross that bridge if I come to it).

The bad news on my latest scan is that the FOLFIRINOX didn’t really work, all of my “drop metastases” grew, my pancreatic pseudocysts grew, and I have a small pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in my lower left lung). Also, according to my latest lab tests, my tumor marker number has risen again, to the 150’s. The good news is that my original tumors (pancreas and liver) are relatively stable, and my doctor thinks it’s time to try experimental treatment, which means immunotherapy. Sometime last year, another CT scan revealed a few different bits and pieces of “worsening metastatic disease,” as my cancer grew and spread. I had and/or have ascites (extra fluid in the abdominal cavity), carcinomatosis (general systemic spread of carcinoma cancer cells), and “nodules,” or tiny little extra tumors floating around in my abdomen. Later on, these nodules started to land in various places and attach themselves to various parts of my insides. As of this latest scan, these nodules, now called “drop metastases” because they’ve literally dropped within my insides due to gravity, have all landed somewhere in my pelvic region, and they’ve all grown. One of these tumors is now 7.5cm in one direction (roughly the size of a clementine?) and is pressing on my bladder. Others are “likely ovarian metastases.” I don’t honestly know whether this means that I now have cancer in my ovaries, or if it’s just little bits of extra cancer on and around my reproductive organs, not necessarily affecting any organ function. Maybe I don’t really want a definitive answer to that question. Regardless, I’m not having any significant symptoms yet from any of these drop metastases, just occasional pelvic pain (like ovulation cramping, which most ladies will understand). And regardless, these extra little cancer bits are raising some complex psychological issues for me, the kinds of conflicting thoughts and worries that I imagine women with reproductive cancers face regularly. And also, I’ve had increased pancreas pain, probably from the growth in the pseudocysts (cystic lesions with a different density and makeup than typical cysts) surrounding my pancreas tumor. All of that means that while the FOLFIRINOX chemo cocktail worked fine on my pancreas and liver tumors, it kind of did diddly squat on a systemic level, allowing these drop metastases to grow way too fast. So David and I crawled through hell four times (those four rounds of FOLFIRINOX), and for what? We’re still here, on the other side, at least. The pulmonary embolism is a surprise. Apparently, though, this happens a lot with pancreatic cancer, which thickens the blood. Fortunately, this one is still quite small, which means we caught it early. The radiologist called my oncologist immediately after the scan, before my clinic appointment, to notify him, so that’s a bit alarming. My oncologist said that while it’s urgent and potentially life-threatening, it’s also very treatable. All I need to do is twice daily shots of heparin (an anticoagulant) for a month, then blood thinner pills for a while. I haven’t had any symptoms from it yet either, which is a good sign. Although now I find myself overthinking my usual breathing patterns, wondering if what I’m feeling any given moment is shortness of breath or not. So far, the shots are going fine. They were icky at first, like the Neupogen shots I’ve done before, with a thick needle on the syringe that doesn’t push into my belly skin very easily. But lately they seem to have gotten easier. I’m about halfway through my month of shots, and I look forward to the end of this chore every 12 hours, and even to the end of the twice daily reminders that pop up on my phone. The positive outcome of this scan is that I finally get to try immunotherapy! I’ve been asking my oncologist about this every clinic visit, and he finally suggested it himself. Now is the right time, because I’ve tried a year of two different chemo regimens. While the first one was very successful initially, this traditional systemic treatment hasn’t been effective enough for me in general. Also, apparently in the last few months, the number of available immunotherapy clinical trials for pancreatic cancer has grown significantly, and there are several new ones at Johns Hopkins itself. David and I researched through the PANCAN clinical trials database and carefully considered our options (at a few Baltimore hospitals, as well as NIH in Bethesda, MD, Georgetown in DC, and Penn in Philadelphia). While we found one we really like at NIH (which I’d prefer to do first, for a variety of reasons), I wouldn’t qualify for our top choice trial at Hopkins if I did this NIH one first. So we decided to go for the Hopkins trial now, and my oncologist is coincidentally the principal investigator. I will hopefully start the screening and enrollment process this week, then start the actual treatment within two weeks from that date. Then it’ll be three weeks on, one week off, with a combination of immunotherapy pills (Palbociclib) and one short weekly chemo infusion (Abraxane). I was hoping to avoid any chemo for a while and do an immunotherapy-only trial, but it seems I might have trouble qualifying for those, because I already have an autoimmune condition, type 1 diabetes. So my hair might fall out again (in which case I think I’ll try out a wig), or it might continue to grow in, which would be a lovely surprise. (I almost have an even buzz cut of new growth now, with this break from treatment.) Fortunately, because I’ll be doing only one chemo drug (as opposed to three or four, as with my previous treatments), the side effects should be pretty manageable. Unfortunately, clinical trials are quite time-intensive and run on regimented schedules, so I won’t have the flexibility I’ve had so far, and I won’t be able to tailor my treatment schedule to my work schedule. We’ll see how it all works out. So for now, we are cautiously optimistic. Immunotherapy is incredibly promising and exciting, the forefront of cancer research and the closest science has come to a cure. In fact, a good friend of mine who works in a cancer research lab and is currently taking a graduate course on advanced cancer biology, just told me yesterday about her professor’s astounding success treating APL leukemia. He’s achieving a 96% complete response (“no evidence of disease,” which is virtually a total cure) in his patients, treating them with high doses of vitamin A (the immunotherapy component) and tiny doses of arsenic (the systemic toxin, or chemotherapy component). These results are absolutely staggering, especially for a cancer that has been notoriously difficult to treat. Of course, all pancreatic cancer, and mine in particular, is generally resistant to treatment, and so far, researchers have not had the same success with immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer that they’ve had for other cancers. But my oncologist did say that research so far has shown that patients who are treated with both Palbociclib and Abraxane have better outcomes than those who are treated with either drug individually. It’s certainly worth a try. As always, I’m consciously working on remaining mindful in the present moment, detaching myself from worries and expectations about the past or the future, and hoping for the best while preparing for the worst. This is the healthiest, most comfortable approach for me, so I’m sticking with it. One day at a time.

2 Comments

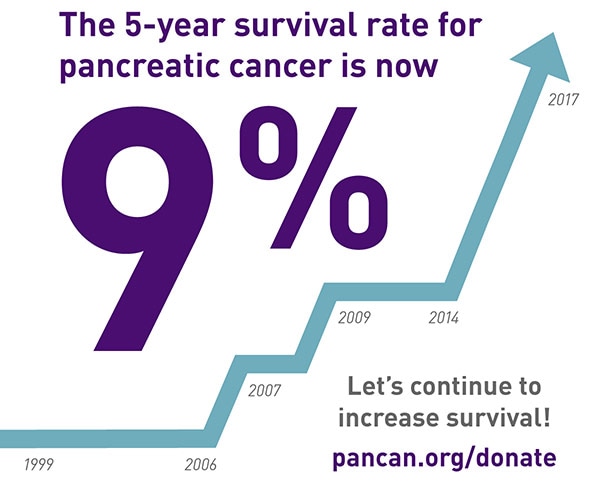

In your first five years of living with cancer, numbers matter. Statistics inform your treatment, your doctor's recommendations, your prognosis, your mood on any given day, and your chances for the future. At the same time, statistics mean absolutely nothing because every individual cancer is independent and unique, and many people defy statistics. Also, if you have a particularly rare form of cancer (or a rare case of a relatively rare cancer, like I do), the shape and path of your cancer is likely not reflected at all in current research. Maybe your case will contribute to research, but that means that the numbers you’ll be able to find (or the numbers your doctor might, eventually, reluctantly reveal to you) really don’t apply to your case at all. You find yourself surrounded by numbers, some encouraging and some decidedly terrifying, but unable to reach out and hold onto to any of them, because there’s a very real chance that not a single one of them matters to your life. This has been my relationship to pancreatic cancer statistics over the last year. I have sought them out, because I’m a naturally curious person, and because I found early on that the more information I had about my new medical reality, the calmer and more confident I felt. I have used them to explain my situation to others, and I have used them to lobby Congress for pancreatic cancer research funding. It is certainly compelling to state dramatically that my cancer, stage IV pancreatic cancer, has a five-year survival rate of only 1%. However, I know that I cannot put any stock in these numbers. Both because they may not be accurate for my particular case, and because putting stock in these statistics is dangerous for my mental health. I can’t let myself think much at all about the possibility that I have only a 1% chance of living to see 2021. I can’t let myself imagine the chance that I might not live to age 35, or celebrate my 7th wedding anniversary, or attend any college reunions past my 10 year. I also can’t let myself worry that I might be in cancer treatment for the rest of my life, or that I’ll never get to have a child, or that I might never be able to get rid of my pancreas and thus slough off this burden that’s weighing me down from the inside. But of course, I do think about all these horrible possibilities. I think about them all the time. Recently, my therapist asked me for a clarifying example when I mentioned that I’ve become much more conscious of my own mortality since my last CT scan, in October, which revealed that my first chemo regimen had stopped working and all of my tumors were growing. I told her that whenever I enter recurring dates in my work calendar, such as my story time assignments on our rotating department schedule or my monthly committee meetings, I find myself casually thinking, oh, might not make it to that one, or I wonder if I’ll still be alive then. These aren’t always negative thoughts, in fact, they’re often neutral, nonchalant musings. It’s not so much that I’m upset by those low-single-digit percentages in all the statistics, but rather that they are the context for how I think about nearly every aspect of my life now. When I make plans for the future, or consider my priorities, or imagine how my life might change over the years, I am always conscious of that five-year frame around my future. In a sense, it has shrunk my perspective down to a smaller box, in which every small thing becomes larger by comparison, and the things that really matter glow so much brighter than they used to. Really, this smaller perspective on the entire span of my life makes it much easier to see quickly what truly matters to me. I don’t have to fumble anymore to figure out my priorities, and it’s easier for me to drop and walk away from the things that don’t make a difference to me in the long run. Because I may not have a long run. In some recent FMLA paperwork that my nurse practitioner filled out for my husband and me, she listed my prognosis as “guarded” and my typical recovery period as “lifelong.” Those two little words can definitely make you stop and clarify your priorities pretty quickly. As I head into what will surely be a telling CT scan on Wednesday (the first since starting my new chemo regimen), I too am guarded. But I’m also living mindfully, cherishing every little moment of my lifelong. I miss this blog when I’m pulled away. Lately, I’ve been pulled away by both good and bad things: work, holidays with families, a long road trip, quality time with my husband, and of course, chemo and its aftermath. I also have a new protocol before chemo infusions, daily Neupogen injections for three days early in the week leading up to my Friday infusions. Neupogen is a bone marrow stimulant, which does appear to be boosting my blood counts well, so that my numbers are high enough for the next round of chemo. Unfortunately, Neupogen causes fatigue and really uncomfortable bone pain, like sharp stabbing pains in my hips, pelvis, and spine. It generally makes me feel like I’m coming down with a bad cold or flu, which certainly isn’t fun when I know I have to end the week with disgusting chemo delirium. Also, the needle gauge on my Neupogen syringes is tricky, and I often have to grit my teeth and slowly push the thick needle in against the resistance of my own belly skin. Let me tell you, that’s the sort of thing that easily gives one the heebie-jeebies. Fortunately, though, I’m on a more regular schedule now with the FOLFIRINOX, going every 3 weeks instead of every 2. This gives my body more time to rebound and rebuild my blood counts, and it gives me a little bit of a reprieve in between rounds. Tomorrow will be my fourth round of FOLFIRINOX, after which I’ll have a CT scan and follow-up with my oncologist. That, finally, will give us some indication whether the FOLFIRINOX is working, or at least working well enough to continue. I’m looking forward to this scan because it’s even harder than I thought it would be to put myself through poison hell without knowing for sure that it’s actually killing my cancer. But I’m also apprehensive about this scan because there’s always a chance it could reveal bad news, and send me right back to the drawing board. I need to be prepared for another shakeup, just in case I do suddenly have to switch chemo regimens again. But as much as I hate FOLFIRINOX, I think I’d rather settle into a routine with it than have to start all over again so soon. So I’m just waiting out my scanxiety, tiptoeing through it one day at a time, until I finally have the next benchmark of answers. And as I prepare to spend New Year’s weekend zoned out and miserable, sleeping and dragging my “baby bottle” of cloudy chemo around on my shoulder until the home care nurse comes, I’m thinking about what it means to bring 2016 to a close. In many ways, this year has been the worst of my life. For many people, in many ways, 2016 has been particularly awful. I sense that many of us are ready for it to be over, thank you very much, and are eager for even a superficial reset in 2017. And of course, for many, the new year always means resolutions. I think I only have two resolutions for 2017: 1) honor my emotions with honesty; and 2) spend more time with friends and family. These are the priorities I find myself prizing nowadays anyway, now that I can’t even begin to guess how much time I have left in this life, and now that every moment of pure existence (especially moments free of medical encumbrances, pain, and side effects) is a sparkling gift. Even though, or maybe because, 2016 has been the worst year of my life, I know it will stand strong in my memory for a long time. I’ve already recounted here a lot of my most memorable experiences from this year, since my cancer diagnosis in January 2016. But there’s one moment in particular that shines bright in my memory already, and I don’t think I’ve told anyone about it before. It was probably late February 2016, after I’d started chemo and before I was ready to return to work. It was in the middle of my worst stretch of pain, treatment side effects, difficulty eating, weight loss, and general wasting away. But, I was somehow able to take a nice, long shower on my own, which felt like quite an accomplishment, and which helped me feel even the tiniest bit refreshed. I played music on my phone while I was in the shower, probably the Future Islands station on Google Play Music. Once I got into my bedroom and started getting dressed, the Arcade Fire song “Wake Up” came on. I first heard this song on the soundtrack to the film Where the Wild Things Are, one of my favorite movies. I’m a children’s librarian, so it shouldn’t surprise anyone that I LOVE Maurice Sendak’s original. I also love the indie hipster film adaptation, which is a bit controversial. About a year after I graduated college, I was working in child care at a fitness center chain, and one of my privileges there once I became a supervisor was to pick which music to play when we opened on Sunday mornings. Without fail, I’d put in my own copy of the soundtrack on CD, and jam out to the wild and weird childish yell-singing of Karen O and the Kids (Karen O from the Yeah Yeah Yeahs). Something about it made me feel carefree and powerful, edgy and whimsical. The soundtrack ends with “Wake Up” by Arcade Fire, and when that song came on my streaming music station that February day, I found myself alone with all my emotions, and with maybe just enough energy to dance around, just a little. I wrapped my arms around myself (my shrinking, shriveling self) and swayed, bobbing my knees slightly. I stretched my neck and legs, gently easing my limbs around, testing the waters of my unfamiliarly frail body. Eventually, as the music picked up, I started to feel looser, warmer, and just a bit stronger. I mouthed along to the words, too winded to sing, and the lyrics hit me. The enormity of what life had thrown at me hit me full force in that moment, and I let myself feel the epic weight of my stage IV cancer. I looked up to the ceiling and opened my mouth in a silent wail. As tears rolled down my cheeks, I extended my arms and slowly turned in circles in my bedroom, bouncing slowly on the balls of my feet. I wept for myself, dancing half-naked and eaten away by cancer, hiding out in my room, away from the world and all its harsh realities. But I also wept with pride, because I was still alive, I was still a person, I was still myself. By the end of the song, I felt, somehow, that I could do it, I could live through cancer, I could come out on the other side, I could be true to myself through it all. And this memory stands out to me now, as I think back on the enormity of 2016, because what I felt in that moment is exactly what has gotten me through this year: "Wake Up" There’s not a lot I can say about the 2016 election that hasn’t already been said. One might argue that I shouldn’t say anything about it, because this is a blog about living with chronic illness, not a blog about politics or current affairs. However, there is a very important reason why I need to discuss the election here: This space is also dedicated to advocating for the rights and dignity of people with disabilities and illnesses, and while those rights and dignity are potentially under attack for the next four years, I will not shy away from the ethical challenges ahead. I will be as political as I need to be to stand up for what I believe. Before we must face those ethical challenges here, though, I want to take some time to consider the psychological and emotional implications of this election for so many people who disagree with it - for roughly half of the country, to be fair. Somewhere in the countless personal accounts and policy analyses I’ve read over the last two weeks, I ran across the metaphor that the election of Donald Trump feels like a cancer diagnosis. Let that sink in for a moment. My first instinct was to take issue at what I thought was a false equivalence. But when I thought about it more, I realized that it perfectly describes my own inner turmoil and heartache at the results of the election. Shock, despair, anger, hopelessness, fear, dread, resolve, adrenaline, and renewed passion. In many ways, it is as if I am living through my own cancer diagnosis again, with a totally different scope and context. It is just as terrifying and heartbreaking as my diagnosis with stage IV pancreatic cancer in January 2016, and no, you don’t get to tell me that I’m being melodramatic or a sore loser. Individual experience is an inalienable right. And I believe there are plenty of others out there who feel that they, too, are living through their own metaphorical cancer diagnoses right now, so I want to give them the space to process their own grief.

You have a day or two, maybe a week if you’re lucky, to process, to let it all sink in, and to make that crucial decision about how to proceed. As you process, you realize that a piece of your heart is missing, that some bit of your core self has been torn out and thrown away. You want to look for it everywhere, but you know it’s a lost cause, it’s already destroyed. Maybe you can slowly build some new little core piece to fill part of that void, but the wound will always be there. You will never forget how much this hurts, how deep the pain cuts. And the disorientation of it all - it’s a fever dream, a nightmare you can’t wake from no matter how hard you pinch yourself. All you want to do is duck your head under the covers and deny it all, pretend it never happened, lose yourself in inane videos of babies and dogs on YouTube, look at pretty curated hipster pictures on Instagram. But that’s only delaying the reckoning, and it doesn’t really make you feel much better because you can’t forget the truth, not even for a second.

You wonder what the next few years will be like - if you even have a few years. You’ve never faced such a challenge before, so you have no idea what to expect. But you have inklings, snippets of other people’s experiences that have stuck in your memory. You tell your friends that if you have to do chemo, you’re going to start smoking pot and wearing turbans, like a classy broad who doesn’t take shit. But the side effects your new doctor told you about are so terrifying, you can’t comprehend them: peripheral neuropathy, crippling nausea, decimated blood counts. And the hair loss that is surely to come, it won’t be pretty. How will you ever feel good about yourself again, when it seems the world is against you, your life has been reduced to a potential, a shaky prognosis? You already don’t feel like yourself anymore. The unpredictability is startling. Sure, life is never really predictable, but at least in the past, you could make plans and generally see them through. Now you wonder if you’ll ever be able to go on a vacation again, because you have to save up all your leave time for sick time, and who knows how long you’ll last anyway? Will you ever get to become a mother, will you make it to your ten year college reunion, will you get to grow old with your spouse in peace? If you have to spend the next few years of your life, possibly all the time you have left, fighting for your very existence, where will the joy be? How will you ever be able to leave the house without doubting your ability to make it back in one piece? How will you go out in public and trust strangers again, without constantly wondering if they’re staring at you, and whether it’s pity or disgust in their eyes? Will you get to have fun, and what will that fun look like, if you’re constantly worried, anxious, afraid? Will your happiness be stolen from you altogether? But then, miraculously, in the middle of all this despair and heartbreak and fearful panic, you realize that people are loving you. Sure, some people only say the wrong thing and continually make you feel worse, like this is your fault, or you’re stupid to be so scared, or grieving won’t help anything, or you’re doing it all wrong. But other people are showing you just how wonderful humanity can be. They’re coming out of the woodwork to say they’re with you, no matter what. They’re showing up, listening, looking you straight in the eye, and saying, “this sucks.” They get it. They’re scared too, they’re sad too. But the way to get through this, the only way that stands a chance, is together, with passion and the courage of your convictions. You hold tight to the hand of the person who is always at your side, the one who loves you no matter how bad things get, the one who understands your pain and admires your conviction. And together, you step forward. You open your mouths and speak the truth. You make the hard decisions and take it one day at a time. You stand up for yourself, your right to live, your eternal dignity. You hold tight to what you know to be true. You resolve that even if you will be reduced to a statistic and ground down to nothing before your time, you will cherish every minute you have left. You will stand up for your principles, the things that make you you, the things that bring you joy, and you will live your best life. Because no one, nothing, not even cancer, can extinguish that flame. Today, Thursday, November 17, 2016, is World Pancreatic Cancer Day. As I continue to process the slew of changes and challenges that have come at me in the last month, I want to take a moment to recognize this day. A worldwide day of advocacy and action like this is dedicated to people like me, and it means a lot to know that so many around the world are working to make my life better. I know I'm thinking of all the other current pancreatic cancer patients, as well as the small but growing number of pancreatic cancer survivors, worldwide. We are a mighty community, united by intimate, painful, and even life-threatening knowledge of this little organ wedged behind our stomachs. I will post again soon, and I've been working on several posts for a while now. I have reached what feels like a turning point in my "cancer journey," where everything takes on a new urgency, and all manner of difficult questions are thrown into stark relief. Everything is okay, though, because I am still here and I am still living my best life every day. About a month ago, my latest CT scan revealed that all of my tumors are growing slightly. This means that the chemo regimen I was on since February, GTX-C, stopped working (because my cancer outsmarted it). So, I've started on a different chemo regimen, FOLFIRINOX, which is just as scary as it sounds. Fortunately, this is standard treatment for pancreatic cancer, and I've met survivors who went into remission thanks to FOLFIRINOX. I've only done one round on this treatment so far, and it was really tough. I think I'm prepared to better manage the side effects for my next round, the day after Thanksgiving. But each chemo infusion is a crapshoot, because the effects are cumulative and there are so many factors that determine how I feel any given day. I definitely have enormous respect for everyone out there who does high-dose chemotherapy on a regular schedule. This all has me thinking a lot about my mortality. Some of these thoughts are terrifying and heartbreaking, and others are shockingly matter-of-fact. I recently read part of the cancer memoir Malignant: How Cancer Becomes Us, by S. Lochlann Jain. The author, an anthropologist and cancer survivor, expresses the unique limbo of a non-terminal cancer prognosis: "How could something be at once so transparent (you will live or die) She also expresses the bittersweet gratitude I've been feeling in huge quantities lately, this joy at the beauty of life in every moment that is so delightful precisely because I know there is a limit to my moments. I want always to be grateful for the moments I do have, even the bad ones, even the tough ones, even the painful ones. All of it is life. "Each morning that I wake up not dead or sick, |

Authorchildren's librarian, Smithie, writer, reader, cook, gardener, cancer patient, medical oddity, PANCAN patient advocate, #chemosurvivor, #spoonie Categories

All

Archives

January 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed